Dickens' Older People in his Transitional and Middle Novels

MARTIN CHUZZELWIT (1842)

PART THREE: THE CAST OF MAJOR AND SUPPORTING OLDER ADULTS: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

It is time to move on from the three principal older character portrayals of Old Martin, Seth Pecksniff, and Sairey Gamp, and focus on other characters, and touch upon those whom we might say are of an uncertain age. (1)

THE TODGERS, MODDLE AND JINKINS MEME

If one were to rely solely on Dickens's narrative portrayals to determine whether a character falls within our definition, one would be in danger of ignoring those adults who are of 'an uncertain age'. Both the illustrations of Phiz and the descriptions and literary context used by this young adult author, especially those who arguably could be in their late middle age, must also be examined. My selections are based solely on what I felt was appropriate; others may take a different view. Nowhere is this more evident than in Martin Chuzzlewit. The narrative description of Mrs Lupin, landlady of the Blue Dragon, suggests an older adult, but the illustration makes it clear she was neither old nor even middle-aged. This is further reinforced by the storyline.

On the other hand, Mr Augustus Moddle, described as the "youngest gentleman" lodging at Todgers, could be interpreted as the youngest of the oldest. Dickens describes him as a youth, but Phiz's illustration identifies him as not young at all. It was, in fact, Mr Jinkins, a bookkeeper, who was the oldest and longest of her lodgers, or was he? If Dickens was simply humorous, was he using old age as a satirical device? Mr Jinkins, described as being of 'a fashionable turn, ' was a regular frequenter of parks on Sundays and knew a great many carriages by sight. He spoke mysteriously of splendid women and was suspected of committing himself to a Countess. (2) He was "a fish salesman's bookkeeper, aged forty' and the senior boarder. One could be a fantasist at any age. So Jinkins falls outside our definition, and Moddle doesn't.

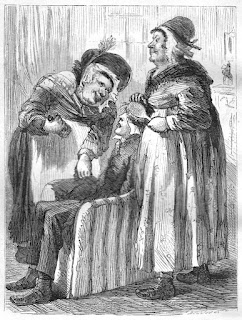

Mr Moddle & Mrs Todgers; 12th Illustration; Hablot K Browne (Phiz). Victorian Web

Yet, here we see a different image of Mr Moddle. Dickens scholars are in a better position than I to explain.

"Mr Moddle is both Particular and Peculiar in his attentions....." Illustration (Phiz)

Victorian Webb

Mrs Todgers, Proprietor of a Commercial Boarding House, again presents a dilemma if we rely purely on Dickens's description. She is portrayed as 'a rather bony and hard-featured lady, with a row of curls in front of her head, shaped like little barrels of beer, and on top of it something made of net, which looked like a black cobweb.'(3) Note 'bony' and 'cobweb.' This, in and of itself, does not necessarily indicate that she is an older adult. Later, Mrs Todgers provides refuge and compassion for Pecksniff's girls, Mercy and Charity. She is a 'kindly soul at heart' (4). In addition, she also befriends Mrs Jonas Chuzzlewit following the suicide of her husband. (5)

So, what is our dilemma? First, the use of particular language could be viewed as implying an older adult stereotype. Second, however, I misunderstood the Moddle and Todgers' illustrations entirely. Does it matter? It is because it evidences a common assumption that, regardless of age, Dickens was not generally gerontophobic. That does not mean he wasn't ageist, which in the three descriptions discussed cannot be ignored as we explore his personal and literary treatment of older people.

I use these three characters to demonstrate the arbitrary nature of assuming chronological age. That said, remembering that it is not uncommon for the perception of old age to be frequently applied to people in their forties, even thirties. If Dickens had been ageist in this regard, it would have again reflected his personal ambivalence or conflict and the beginnings of his age anxiety. Moreover, he had yet to confront his age-related embarrassment and angst in the 1850s and 1860s. He did not want to be seen as old, pitied, or labelled. The irony is that, by and large, he was. His letters indicate that he became increasingly conscious of his age, expressing humour, resignation, and even defiance. The notion of Dickens's premature ageing, caused by overwork, remains a topic of discussion and is still given credence today.

'Mrs Todgers and the Pecksniffs call upon Miss Pinch'. ( Illustration by Phiz) The Dickens Page

MR CHUFFEY:

There is no ambiguity about this clerk to Anthony Chuzzilwit, depicted as 'a blear-eyed, weazen-faced, ancient man'. He was of a remote fashion, and dusty like the rest of his furniture; he was dressed in a decayed suit of black, with breeches garnished at the knees with rusty wisps of ribbon; the very paupers of shoestrings on the lower portions of his spindly legs wore dingy worsted stockings of the same colour.' (6) Philips and Gadd note in their Dictionary that Chuffey 'is so wrapped up in his master that he seems dead to the world' (7)

On the death of his master, Chuffey goes to live with Jonas and Mercy Chuzzzlewit, for whom he conceals a secret adoration (note not admiration). Jonas is wary of his father's Clerk, fearing he may have discovered the plan to murder him. Jonas hands him over to Gamp, who reports back his worst nightmare. She believes Chuffey knew of his murderous plan. Gamp is advised to treat Chuffey as if he were mentally ill, but the plot, in any event, is exposed, Chuffey owns up that he knew about it, and Anthony Chuzzliwit is heartbroken. The fact that Anthony had actually died of natural causes is unknown to Jonas, who believed he had actually committed patricide, which placed him in the blackmailing hands of Montague Tigg. It did not go well for Tigg, who was murdered by Jonas, nor for Jonas, who, having been arrested, died by suicide. Dickens later defended his characterisation of Jonas, writing, "I claim him as the legitimate issue of the father upon whom those vices ( ie cunning, treachery, avarice) are seen to recoil" (8)

Old Chuffey: Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Alamy

(Image: D3HWF)

Dickens's general portrayal of clerks is sympathetic. In Chuffey, Dickens criticised his exploitation by the family, which in turn reflected his criticism of societal structures. As we have seen previously, Dickens was the son of a clerk and thus experienced the precariousness of that employment. Indeed, he was a law clerk for a while in his professional/occupational life, and before Boz's success, it was tedious. We have already discussed Dickens's early novels through our analysis of Tim Linkwater (Nicholas Nickleby), Mr Lowten ( Pickwick Papers), and not forgetting the iconic Bob Cratchit (A Christmas Carol), the latter of which was seen in the context of Ebenezer Scrooge. Dickens was confronting workplace abuse, social values and the social and economic systems that existed. However, he also acknowledged that, by and large, older clerks could be absorbed into family structures and treated kindly, if not paternally or maternally.

Dickens knew that they comprised the lower middle classes, who were on a barely living wage, and Chuffey, without the generosity of the likes of the Charles and Edwin Cheeryble brothers (Nicholas Nickleby), was dealt an awful hand. Loyalty was rewarded by neglect and abuse.

DR JOHN JOBLING: (Of Uncertain Age)

This character is difficult to call in terms of age. He was unscrupulous but agreeable. (9) Jobling attends Anthony Chuzzilwit's funeral at Jonas's specific invitation to deflect any suspicion or suggestion that he had poisoned his father. He is also a physician to the young surgeon Lewsome, who is under the care of Sarey Gamp, God help us. Surprisingly, I would add, Lewsome recovers and confesses to a friend that he had supplied Jonas with the poison, which he also assumes implicated him in the death of Anthony Chuzzzlewit.

We are informed that "(His) neckerchief and shirt-frill were ever of the whitest, his clothes blackest and sleekest, his gold watchchain of the heaviest, and his seals the largest. His boots, which were always the brightest, creaked as he walked" (10)

Later, Dr Jobling becomes the Medical Officer to the fraudulent Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan & Life Assurance Company, which Montague Tigg set up. As Hawes reminds us, "Jobling was far too knowing to connect himself with a company in any closer ties than as a well-paid functionary, or to allow his connections to be misunderstood abroad, if he could help it."(11)

Given that Dickens does not provide an exact age, we may gain insight or a clue by examining his relationships with other characters, including Gamp, Pecksniff, Tigg, Anthony, and Jonas Chuzzlewit. On balance, possibly in his 40s or even 50s, but though still of uncertain age, it was necessary to include him in our analysis of older adult characters. (12)

MR NADGETT: ( More a 'Columbo' than 007 ?)

Illustration: Sol Eytinge (1867). Image by Philip V Allingham: formatted by George. P. Ladlow. The Victorian Webb

Nadgett was Tom Pinch's landlord in London and employed by Montague Tigg as an investigator. We are on firmer ground regarding his status as an older adult. Indeed, Dickens is uncompromising and vicious in his physical portrayal, described as "a short, dried up, withered old man, who seemed to have secreted his very blood; for nobody would have given him credit for possession of six ounces of it in his whole body."(13) Dickens goes further in emphasing Nadgett's oldness: "He was mildewed, threadbare, shabby; always had fluff upon his legs and back..."(14) Hawes, sourcing Philip Collins posits that "Nadgett is the earliest elaborate example of an amautur detective in Dickens's works: 'he moves in the meloddramatic atmosphere of mystery, diligence, patience, and uncanny perceptiveness,' "(15) Thus we could argue his description belies intellectual and cognitive qualities, and for those readers today, themselves of a certain age we are reminded of the highly aclaimed TV detective series Columbo between 1971-1990. (16)

Some argue that without Nadgett, there would not have been a Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple. This is a step too far, but there is no doubt that Dickens was an early pioneer of detective fiction and Nadgett a significant creation. (17) The intersections, however, of his role, his physical portrayal and his age have not been sufficiently explored by Dickensian writers past and present. He may not have been a Columbo, but in terms of his secret agent mission to expose the naffairance of Jonas Chuzzlewit, he was not a 007 either.

Mr Nadgett breathes as an atmosphere of mystery.Illustration by Hablot Browne (1843-44)

Which brings me to an intriguing possibility. Was he, in fact, in disguise to aid him in his role, and thus to be invisible and unnoticed as he gathered evidence of a crime? Dickens's description, however, is too detailed; the storyline does not support the notion, as surely Dickens would have played with his readers by a 'big reveal'. It would have aligned him with Pecksniff, Jonas, and Old Martin himself, all of whom were concerned with appearance and behaviour to mask and deceive for good or ill. (18) Nevertheless, it is an interesting, if not a highly improbable proposition. Agesim, however, is evident. The exaggerated stereotyped description of old age and invisibility was, as now, a common assertion. The notion that old age equates to mental infirmity, dated dress sense, or age-inappropriate behaviour is the staple fare of theatre, comedy, and media presentations. Dickens employs this technique to significant effect in his writings, thus enhancing his narrative function. I do not, however, accept that this was in play in the portrayal of Nadgett. That does not mean the character's portrayal was not fundamentally ageist in terms of the language or the evident intersections. Gamp was a case in point.

MRS NED CHUZZLEWIT

Widow of old Martin's brother, and described as a disagreeable woman who outlived three husbands. Her three daughters were all spinsters and "very masculine looking". She would probably be in either her late middle age or even early "green age", a 19th-century term which we have discussed previously. He also added that she had a dreary face and a bony figure. (19) There is no Hablot Browne (Phiz) illustration of this character, and she can, after all, be regarded as a minor one at best. However, do the minor female characters reveal more about Dickens's attitude to older women than the exploration of his major ones? Much has been written about Dickens and women, but very little attention has been paid to the context of ageism, gender bias, and Victorian attitudes towards age and ageing.

Edward Guiliano's Edited Dickens & Women ReObserved is a homage to Michael Slater's seminal study, Dickens and Women, published in 1983, (20)(21) which will be discussed as we journey through Dickens' middle and later novels as he ages. Let Mrs Ned and other previously discussed older adult minor or supporting characters be a marker.

GEORGE CHUZZLEWIT ( Of Uncertain Age)

This 'gay bachelor cousin of Old Martin Chuzzlewit is interesting in that Dickens writes that 'he claimed to be young but had been younger, and was inclined to be corpulent and rather overfed himself.' (22) This notion of being young is associated with being older and 'inclined to corpulence' is worth pondering. The role of language is evident in both Dickens' early and middle novels, revealing that ageist communication plays a central part in his portrayals of older adults. George Chuzzilwit is a case in point. Age-related comments, including narrative asides, or, as Robert McCann and Howard Giles call them, 'stray remarks,' can generally reflect the prevalence of ageism in society at large. (23) The authors were specifically writing about ageism in the workplace, but it can be applied to literature, albeit with a different burden of proof. It is worth remembering that our thirty-one-year-old writer would never have conceived that his writings were ageist (or even cared?) as the concept did not exist, but that does not mean that the 'youth-old' comparison in terms of Victorian attitudes did not reflect the belief that being young was a much preferred position than being old. But as Joy Wilkinson and Kenneth Ferraro contend, "ageism is generally thought to be both negative and positive, which would reflect prejudice or discrimination in favour of older people"(24). Today, I would define this as 'compassionate ageism', which, in my view, underpins the 'othering' of older people, whether within the family, an institution, or the workplace. If, at the end of the day, we constantly compare young with old, and we even talk about ourselves as X years Young, we have internalised young/old prejudiced attitudes and discrimination regardless of our conscious intention.

If George clung to his younger self, it was a simple reflection of his need to avoid old age. If we take a periodological view of history, Dickens held a Victorian position, holding both a negative and positive view of old age and ageing. He reflected, whether acknowledged or not, the complexity and multidimensional nature of age and ageing. His characterisations of older people confirm this. Margaret Gullette tells us that ' we cannot slide into another's life course, can never wrap ourselves in their experience of ageing.' (25) A salient point, especially given this book's proposition.

"THE MATCHMAKER" ( A Matron of Uncertain Age)

Another minor character who is hardly listed in various Dickens Directories. She is, however, referenced in Philip and Gadd. (26) Described by Dickens as a 'Matron of such destructive principles, and so familiarised to the use and composition of inflamatory and combustible, that she was called the matchmaker, by nickname and a byword she is recognised in the family legends of today'. (27) The Literature Network Website notes that she is a Spanish lady who marries a Chuzzlewit in Spain, who became involved in the English Gunpowder Plot in 1605, possibly even carrying the lantern.

Whilst the term 'Matron' was generally associated with middle age in the nineteenth century, it was also held in a position of authority and could carry a slightly old fashioned tone, but was also used in a derogatory or satirical sense to portray an overly stern, domineering woman. (28) Dickens' reference to the character should be seen in the context of his first chapter's chronology of the Chuzzlewit family ancestry. It was a comic and tongue-in-cheek satire, claiming a long, distinguished history that dated back to Adam and Eve, and that successive generations were involved in the 'bloodiest events', and even received rewards from the Norman Conquest (1066). The common thread running through their history was one of opportunism, greed, and villainy. This was Dickens' intention. It was a masterful context for introducing the family and its bearing on the unfolding plot(s). (29)

The association with the Matchmaker and her portrayal, relating to chronological or even generational age, is tenuous, but excluding the possibility would have been mistaken. The association with the term 'matron' is my rationale.

The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators at Work Housed of Parliament Alamy [ ID 87ECM1]

MR AND MRS SPOTTLETOE

This couple were relatives of Old Martin and Mr Spottletoe is referred to 'as being bald, but had such big whiskers that he seemed to have stopped his hair, by the sudden application of some powerful remedy, in the very act of falling off his head, and to have fastened itirrevocably on his face' (30) It was also said that that he was hot tempered and married into the Chuzzlwit family.

Mrs Spottletoe's description is from our point of view interesting, given the commentary on George Chuzzlewit, namely that she was ' much too slim for her years and of a poetical constitution' (31) It is further noted that she was 'accustomed to inform her more intimate friends that she said Mr Spottletoe was the loadstar of her existence' (32)

Mr Spottletoe stands up to Mr Pecksniff.

Illustration by Harry Furniss. Library Edition. Published by The Educational Book Company Ltd., Edited by J.A. Hammerton (1910)

[Note the illustration of Mrs Spottletoe seated]

Their role, being part of the Chuzzlewit clan, was certainly to reinforce their own greed, but also to challenge Pecksniff's connivance in Old Martin leaving Salisbury and having summoned the family under false pretences. (33) They are predatory, convinced that Old Martin is at death's door, rushing to his bedside in the hope of financially benefiting from his demise. Illustrator Furness's image clearly places them in the cast of Dickens' older people.

MAJOR AND MRS PAWKINS

The supposition here, and hence inclusion, is based on the Major's experience in both commercial and political affairs. Of course, Dickens may have had in mind an early middle aged character. The Major was a Pennsylvanian, and his wife was the landlady of yet another boarding house where young Martin stayed.

We have already discussed Dickens' experience and opinion of America and Americans, thus the description of the character resonated with his far from flattering opinion. Given that the American adventure narrative was occasioned by his desire to improve readership numbers, which, given his precarious financial circumstances and debt to the publishers, was understandable. Consulting, however, the renowned Dickensian scholar Paul Schlicke, the fact that in his Martin Chuzzlewit Section ( Sources and Context), the list of contemporary sources excludes this particular character. (34) Thus, Dickens's portrayal becomes our only primary source. Of the Major, " he was distinguished by a very large skull, and a mass of hair" (35). Furthermore, he had "a heavy eye, and a dull, slow manner-with a most distinguished genius for swindling" (36). Mrs Pawkins was "very straight, bony, and silent" (37), and to top it all, the Major, Dickens added, "rather loafed his time away than otherwise"

PROFESSOR MULLIT ( Of Uncertain Age)

Professor of Education and a fellow boarder with Young Martin of Mrs Pawkins's New York lodgings. We learn from another boarder, the gossiping Jefferson Brick, that Mullit, despite his ' fine moral elements', had repudiated his own father for voting for the wrong Presidential candidate. Mullit was proud of the abandonment as he later used the pen name 'Sturb' (37)(38)

I was unable to locate an illustration from the novels' various reprints, which probably reflects the fact that he was a minor character, but was portrayed again to highlight hypocrisy and Dickens' own knowledge of Ancient Roman history (38) . He perhaps thought it was not worth an illustration-unless a reader can direct me to one! Dickens, as we have previously noted, controlled and directed all his illustrators (39). Even John Forster stated in his Dickens' seminal multi-volume biography that he was not easy to please (40)

MR AND MRS NORRIS, CICERO AND NORTH AMERICAN SLAVERY

Mrs Norris, writes Dickens, was 'a woman who looks older and more faded than she ought to'. Regarding Mr Norris's mother, she was 'a little sharp-eyed quick old woman'. In terms of the storyline, Dickens places them in New York, where they are snobs and, though claiming to be abolitionists, still believe that slaves (called blacks) belonged to an inferior race. (41)

Dickens introduces the character Cicero, whose age is not identified but is described as a 'former black slave who eventually purchased his liberty and was saving money to buy his daughter's freedom. (42) We know that his own liberty was achieved 'on account of his strength nearly gone, and being ill.' (43) Young Martin and Mark Tapley meet him whilst in New York. Dickens's narrative spells out the treatment of slaves through the character, namely, he was 'shot in the leg, gashed in the arm, scarred in his live limbs' like a crippled fish, beaten out of shape, had his neck gutted with an iron collar, and wore iron rings upon his wrists and ankles' (44) Cicero's age is irrelevant ( according to the illustrations he was not an older adult) but we need to consider that his portrayal and that of the Norrises tell us something about Dickens's view on slavery as he wrote both American Notes and Chuzzliwit (1843-4). Although I touched upon this previously, it is helpful at this point to elaborate further, given his portrayal of the Norrises and Cicero.

'Mr Tapley succeeds in finding a Jolly Subject for Contemplation'

' (Phiz) 1844 edition. Scanned image by Philip V. Allingham. Victorian Web. (Modified 11.01.2019)

Professor Philip Allingham's Victorian Web posting provides an invaluable analysis in this regard. (45) He rightly refers to Dickens's early career as a Parliamentary reporter in that he failed despite his radical politics, said 'nothing whatsoever in print about slavery' (46)

Slavery in the British Empire was legal, and even the philanthropist Mr Brownlow (Oliver Twist) owned plantations in the West Indies. Allingham states that there was not one word from Dickens expressing abolitionist solidarity. He would, however, a decade later, write in Household Words that 'emancipation in a way that would be wiped out every reproach for the past treatment of the negroes' (47) He did not, when fretting about the lack of copyrite on this his first visit and at any stage ' publically state his feelings about slavery until after his return to England, in a chapter and an adendum in American Notes' (48) That said, though he was silent even whilst visiting the Southern States and its' plantations we know that he was absoultly repulsed by it. Was that silence a reflection of not wanting to upset his hosts? Dickens, clearly, for whatever reason —out of courtesy or to protect his income —saved his animosity, like stamps in Transactional Analysis, using Martin Chuzzlewit to cash them in through the portrayals of the Norrishes and Cicero. Allingham says, 'in depicting Cicero in a positive light, Dickens and Phiz were casting their lot with the abolitionists as to whether the American negro should enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or whether he or she was mearly some white American's personal property' (49) The sales intersection between American Notes and Martin Chuzzlwit had clearly played out in his appeasment, having great expectaions for commissions from American publishers. (50) Dickens was, without doubt, with the abolitionists in spirit, but at heart, very much a Victorian businessman; the purse won.

Fred Barnard's realisation of Martin's meeting Cicero. Household Words. Edition ( 1872). Note the date- two years following the death of Dickens

Readers might reasonably ask whether Dickens expressed anti-slavery sentiment in his private correspondence. In February 1842, he wrote to John Forster. He said he would receive 'no public mark of respect in any place where slavery was'. Such was his disgust that he confided in his letter of his decision to abandon the Southern States tour and travel on to Charlesdon. In addition, writing at the same time to William Macready, of the 'cruel racial repression' he witnessed (51). It is worth noting, however, that both in public and private, he did not challenge the very British colonial foundation of American slavery. Dr Md. Mahamul Hasan is unforgiving and damning, claiming that Dickens was at this time enjoying a wider popularity of praise and admiration than any other author, even though he condoned colonial exploitation and that 'no one censored him then for his unprincipled and opportunistic stance' (52)

New Orleans, Louisiana. The Transatlantic Slave Trade. eji.org

MR MOULD

Mr Mould carried out the funeral of Anthony Chuzzlewit, and was described as 'a little bald elderly gentleman'. Not surprisingly, he wore a black suit and Dickens adds that his 'queer attempt at melancholy was at odds with a smirk of satisfaction.' With a large notebook in hand, he wore a 'massive gold watch chain dangling from his fob'. Mould was a comfortable family man with two daughters, - 'plump as any partridge was each Miss Mould, and Mrs Mould's plumper than the two together'. (53)(54) He was, in fact, a 'placid, cheerful man', says Dickens.

The job, the family and even the description of his premises conjure up a positive image of old age. There is, nevertheless, in typical Dickens fashion, another character lurking within Mr Mould, one that is a commentary on Victorian undertakers. Mould is in cahoots with Sairey Gamp, whom he regularly recommended to grieving families; he both benefits and exploits. We also need to take into account the business mask of mournful sorrow that Mould adopted. At the funeral of Anthony Chuzzilwit, Dickens writes of Mould's employees, that his men 'found it necessary to down their grief, like a young kitten in mourning of its existence, for which reason they generally fuddled themselves before they began to do anything, lest it should make head and get the better of them. In short, the whole of that strange week was a round of dismal joviality and grim enjoyment ...who came in the shadow of Anthony Chuzzilwit's grave, feasted like a Goul'. (55)

Mould was, in reality, a ghastly and unsympathetic character who profited from people's grief. (56) It is claimed that, generally, Dickens portrayed undertakers in this manner as it reflected his low opinion of them and the trade. Interestingly, they were, for the most part, older adults. Mr Sowerberry (Oliver Twist), Mr Trabb (Great Expectations), and implied in A Christmas Carol. A more positive portrayal is that of Mr Omer (David Copperfield). Still, his description is worthy of note, namely 'a fat, short-winded, merry-looking, little old man in black, with rusty little bunches of ribbons at the knees of his breeches, black stockings, and a broad-brimmed hat.' That said, he was represented as a genuine and caring older character.

Undertakers generally at this time had other occupations, be that cabinet making, and in the case of Mr Omer, draper, tailor, haberdasher and furnisher.

Image gallery: trade card /print. Victorian. www.pinterest.com

MR TACKER (An Official Chief Mourner of Uncertain Age )

It seems appropriate, before leaving Victorian funerals and undertakers, to note this very minor character. In The Dickens Index, he warrants only a six-word line (57). Hawes, in a single paragraph, effectively highlights Dickens' portrayal. ' He was obese, had a bottle nose and a face covered in pimples', perhaps inferring a teenager or a young adult. However, Tacker had 'run to seed' and though his age is by no means specific, Dickens includes further commentary. Tacker ....' who, from his great experience in the performing of funerals, would have made an excellent pantomime actor' (59)

MR LAFAYETTE KETTLE, GENERAL CYRUS CHOKE and ZEPANIAH SCADDER - ( A Trio of Fraudsters)

'The thriving City of Eden, as it Appeared on Paper' By Phiz (1834)

It is necessary from the outset to acknowledge that the character of Scadder, when based on Phiz's illustration (below), falls outside of our definition of an older adult (50-plus). Both Kettle and Choke, if I were to adhere rigidly to that chronological threshold, would not be considered in our analysis of older people either. The rationale for their inclusion is, first, their importance in the fraud against Mark Tapley and Young Martin, who were both young adults; second, the notion of their being naive (inverse ageism); third, the common belief that older adult 'criminals' of any age contaminated or exploited younger adults; fourth, a more crucial but general point, in that defintions of an older person was, in the Victorian era not defined in socio- economic terms ( ie becoming a pensioner). Ultimately, the transition from middle age to old age is a fluid demographic concept based on multiple factors. This is further compounded by the fact that, whatever age you are, old age is, more often than not, perceived as twenty years older than you. They, in fact, become somebody else. In this section, I will reflect on the concept of age-differentiated behaviour and language to help us understand how Dickens may have used these particular portrayals and the intersection with Dickens' cultural bias and questioning if age bias was evident.

Dickens's portrayal of Kettle is said to be 'one of the most typical of caricatures of American personalities.' (60) Depicted as 'Languid and listless in his looks, his cheeks were hollow that he seemed to be always sucking them in: and the sun had burnt him not a wholesome red or brown, but dirty yellow. He had bright, dark eyes, which he kept half closed' (61). Young Martin and Mark Tapley meet him on their journey to Eden, a midwestern American colony of Dickens' imagination, which was prompted by a settlement of Cairo, Illinois, on the banks of the Mississippi. Eden was promoted speculatively as a good investment. It was a con. Young Martin fell for it when he discovered that the plot he had purchased was actually a swamp.

Kettle was Secretary of the Watertoast Association of United Sympathisers, a pro-Irish organisation, and its animosity towards the English was a key motivator for its members. (62) Enter General Cyrus Choke, the fraudulent and calculating land agent in Eden, aided and abetted by Zephaniah Scadder. The conjunction of these two with Kettle is relevant. Unfortunately, Dickens does not help me here, as he fails to provide any indication as to their ages in his descriptions, which could lead us to say he was anti-ageist. Arguably, Kettle may have been unprepossessing (an indicator of a conman), as his intrusion on Mark and Martin suggests that he was 'grooming' his targets.

General Choke is described as a gentleman, howbeit ' very lank ...in a white cravat, long white waistcoat and a black greatcoat.' (63) Having (allegedly) been a General implies he was using his senior rank to give his targets a sense of confidence that he could be trusted, part of the con. He chaired the Watertoast Sympathisers.

As for Scadder, Dickens provides his usual full description of physical appearance and demeanour, but surprisingly without reference to his age. 'Two grey eyes lurked deep within this agent's head, but one of them had no sight of it, and stood stock still. With that side of his face, he seemed to listen to what the other side was doing. Thus, each profile had a distinct expression, and when the movable side was most in action, the rigid one was in its coldest state of watchfulness. It was like turning the man inside out, to pass to that view of his features in the liveliest mood, and see how calculating and intent they were' (64)

Scadder also wore a white open necked shirt, and 'every time he spoke, something was seen to twitch and jerk up in his throat, like the little hammers in a harpsichord when notes are stuck. Perhaps it was the Truth feebly endeavouring to leap to his lips. If so, it never reached them.' (65) Dickens continues that 'Scadder had long black hair upon his head, hung down as straight as any plummet line' (66)

General Choke (standing) and Mr Scadder.

Image scan by Philip V. Allingham: formatted by George P. Landow ( 1867)

The Victorian Web

This trio of fraudsters were clearly not even in their 'green' years of old age, nor were they illustrated as such. However, can the narrative description with these characters be interpreted as age-differentiated? (67) Dickens certainly, through his literary narrative here, portrayed cultural, gender, and, I would add, age stereotypes and prejudice. Some may find this absurd.

Levy and Banaji rightly assert that ' one of the most insidious aspects of ageism is that it can operate without conscious awareness, control, or intention to harm'. (68) This can lead to unnoticed or uncontrollable prejudice. (69) Dickens did not hate older people; he was simply ambivalent. That unconsciousness and ambivalence, his view of older adults and hence portrayals were therefore unregulated. Dickens was at this time a young adult himself and may have been younger than Kettle and Choke; the jury's out concerning Scadder. That acknowledged, their descriptions raise the possibility for me. What is relevant, however, is the intersection of his bias against American behaviour and implied ageism, which cannot be ignored. Their descriptions tend to lean towards cultural negativity, regardless of their perceived ages. Let me explain further. Age-differentiated Behaviour and Language have their roots in how society constructs age and how it collectively thinks about older people.

'Victorian London was both filthy and rich, published by Look & Learn. Downloaded 25.06.15

England operated within differentiated constructs related to class, race, gender, and, at the time of Dickens' writing, his early novels and this transitional work, I suggest, must also include age in those formulations. The alignment of Victorian stereotyping, literature, and theatre (in fact, all the arts), as well as power dynamics within society and families, and a lack of awareness of 'implicit ageism', shaped how Dickens portrayed older people.

Image of the lifestyle of rich Victorians Pinterest.com [Downloaded 25.06.25

MRS BETSEY PRIG; 'The Best of Creeturs'

Mrs Prig was a companion to Mrs Gamp, and whilst another minor character, we are on firmer ground. She was a nurse at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London and resembled Mrs Gamp 'in her slatterney ways, brutal behaviour towards patients, and ignorance of elementary nursing procedure' (70)(71). As with Gamp, Dickens used her to expose the neglect and abuse of patients within hospital and community settings. They were mirror images of each other, old, neglectful, and exploitative. Prig 'was of the Gamp build, but not so fat; and her voice was deeper and more like a man's. She also had a beard' (72). Hawes notes that Dickens wrote in 1849 that ' hospitals of London are in many respects, notable institutions; in others, very defective. I think it is not the least among the instances of their mismanagement that Mrs Betsey Prig is a fair specimen of a Hospital Nurse'. (73)

Sairey Gamp and Betsey Prig.

Sol Entinge, Jr. (1867). Image scanned

by Philip V. Allingham: formatted by

George Landow. Victorian Web

[The unfortunate patient is Mr Lewsome

a young surgeon abused by Gamp and

Prig ]

Mrs Gamp proposes a toast.

Illustrated by Phiz ( 1844). Scanned by

Philip Allingham . Victorian Web

BY WAY OF CONCLUSION

'There are a number of decent, upright characters in the book - but also a host of unlikable folk steeped in various degrees of malevolence and selfishness', write Stephen Browning and Simon Thomas (74). Considering those we regard as Dickens' older characters, as well as those of uncertain age, he has provided evidence of at least generational diversity. In trying to get behind the older characters and interpret them in Dickens' own time and place through a 21st-century lens, we are faced with a significant number of challenges, not least of which are the interlocking biases of Dickens, of Victorian society and its literature, but also of literary and social gerontologists of today. The first challenge that a social scientist and even a social worker faces is to confront their own personal and professional biases. Periodisation, Implicit Ageism and Age-differentiation, which I have referenced, are tentative concepts to explore an understanding of Dickens' older characterisations, as well as Dickens himself.

My own detour into the American characters has been particularly challenging, and, on reflection, ought to be explored further at another time, as they reveal more about Dickens and his portrayals than I initially thought.

Let me conclude by quoting Jesper Soerensen in his exploration of Martin Chuzzlewit: ' Fiction is but a tame imitation of the wild truth' (75)

Never a truer word!

[The next in this blog series, 'Dickens' Older People: His Transitional and Middle Novels', wll be his seventh novel, Dombey and Son (1846) ]

SOURCES, NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. THE LITERATURE NETWORK A comprehensive online resource of some 3,500 publications. www.online-literature.com

2. HAWES D. 'Who's Who in Dickens' Routledge. London & New York (1998) (p.121)

3. Ibid. HAWES. (p241)

4. BENTLEY. N, SLATER. M, and BURGIS. N. 'The Dickens Index' Oxford University Press. (1988) (p 262)

5. Ibid. BENTLEY et al. (p262)

6. PHILIP. A. and GADD, L. 'The Dickens Directory' Bracken Books. London. (1989) (p57)

7. Ibid PHILIPS & GADD. (p 57)

8. Ibid HAWES (p42-43)

9. Ibid. BENTLEY et al. (p 134)

10. Ibid. HAWES. (123)

11. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. (p 157)

12. Ibid. THE LITERATURE NETWORK

13. Ibid. HAWES. (p 161)

14. Ibid. HAWES. (p 161)

15. COLLINS P, 'Dickens and Crime' 2nd Edition. MacMillan. London (1964) in HAWES. (p 161)

16. COBAIN. D. Available on Danecobaine.com/ Reviews (date unknown)

17. HAINING. P (Ed) 'Hunted Down. The Detectives' Stories of Charles Dickens, Peter Owen Publishers. Introduction and Chapter One: 'Nemesis'. An Anthology. (1996) ( p7-44)

18. I used an AI (GROK) to ask what the intersections were between Nadgett's description and role. It had not crossed my mind that it was a pretence - in that he deliberately dressed in a way that made him invisible. Grok searched 15 sources. I am not persuaded.

19. Ibid. PHILIPS & GADD. (p66)

20. GUILIANO, E (Ed.) 'Dickens & Women ReObserved' Edward Root Publishers. Brighton. (2020)

21. SLATER. M. in GUILIANO.

22. Ibid. HAWES (p42)

23. McCann, R. and GILES, H. 'Ageism in the Workplace: A Communication Perspective'

Chapter Six. in NELSON.D.TODD (Ed). 'Ageism -Sterotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons'. A Bradford Book. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass. London. Massachusetts (2004) (p 340)

24. WILKINSON. J.A. and FERRARO. K.F. 'Thirty Years of Ageism Research' Chapter 12. in McCANN & GILES (2004). (p 340)

25. GULLETTE. M.M. 'Agewise: Fighting the New Ageism in America' The University of Chicago Press. Back Cover blurb. (Health) (2011)

26. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. (p190)

27. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. (p 190)

28. GROK AI. Asked what the term Matron meant in the 19th century (Downloaded 11.06.24)

29. Ibid. THE LITERATURE NETWORK. Summary Chapter One.

30. Ibid. HAWES. (p 225)

31. Ibid. HAWES. (p225)

32. Ibid. HAWES. (p225)

33. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. ( p 273)

34. SCHLICKE. P. (Ed) 'Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens: Martin Chuzzlewit. (2000) (p. 376)

35. Ibid. BENTLEY et al. (p 192).

36. Ibid. PHILIPS & GADD (p 219)

37. Ibid. HAWES. (p 137)

38. Ibid BENTLEY et al (p 36). Under the heading "BRUTUS REVERSED," both HAWES and BENTLEY reference Lucius Junius Brutus, who played a role in the expulsion of the ruling Tarquin family and condemned his own son to death for attempting to reinstate the Tarquins.

39. THE DICKENS PAGE: Illustrating Charles Dickens.. Copyright PERDUE.D. (1997-2025) Updated 28.08.23.

40. FORSTER, J. Vol 2. (p 28-31) Quoted Ibid. THE DICKENS PAGE.

41. Ibid. BENTLEY et al. (p 180)

42. Ibid. HAWES. (p 43)

43 . Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. (p 61)

44. Ibid. BENTLEY et al ( p 54-55)

45. ALLINGHAM. P. 'Charles and Dickens and American Slavery, 1842 - 52' The Victorian Web. Modified. 11.01.2019.

46. Ibid. ALLINHAM. (p1)

47. Ibid.ALLINGHAM. Quoting DICKENS Household Words (18 September 1852. (p 5)

48. Ibid ALLINGHAM. (p1)

49. Ibid ALLINGHAM (p 3-4)

50. Ibid. ALLINGHAM ( p4)

51. Ibid. GROK. In response to the question of whether Dickens expressed his anti-slavery sentiments in his private letters while in America (1842-3), it included a letter written to Captain Denham (discovered in 2022), a Royal Naval Officer engaged in the African blockade. Dickens is uncompromising in his condemnation.

52. HASAN, M. Md. ' Charles Dickens, Colonialism, and the Slave Trade. The Daily Star. (02.06.24)

53. Ibid. PHILIPS & GADD. (p 201)

54. Ibid. HAWES (p157)

55. THE VICTORIAN WEB. 'Funerals and Undertakers in Dickens' Novels' Created 19.02.2015.

56. THE VICTORIANIST; Victorian Undertaking - A Plea.... Author unidentified. Posted by The Amateur Casual. (2010)

57. Ibid. BENTLEY etal (p255)

58. Ibid . HAWES. (p 234)

59. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. (p 282)

60. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. ( p 161)

61. Ibid. PHILIP & GADD. ( p 162)

62. Ibid. BENTLEY et al. (p 278)

63. Ibid. BENTLEY et al (p 52)

64. Ibid. BENTLEY et al (p227)

65. Ibid. HAWES. (p 206-7)

66. Ibid. HAWES ( p 207)

67. LEVY. B.R. and BANAJI. M Implicit Ageism. Chapter 3 in Ibid TODD. T (Ed) (p 51)

68. Ibid LEVY & BANAJI (p 50)

69 Ibid. LEVY & BANAJI (p 50)

70. Ibid. PHILIPS & GADD. (p235)

71. Ibid BENTLEY et al ( p 206)

72. Ibid. HAWES. (p 189)

73. Ibid. HAWES. (189)

74. BROWNING. S and THOMAS. S. The Real Charles Dickens. White Owl (2025)

(p 73-74)

75. SOERENSEN. J. 'Charles Dickens- Stories of His Life' Olympia Publishers. London. (2023) (p 131-2)