DICKENS OLDER PEOPLE: The Portrayal of Older Adult Characters in his Novels

Novel Five

BARNABY RUDGE: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty' (1841)

PART TWO: THE CAST OF OLDER ADULTS: MEETING 'THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY'

Taken from Charles Dickens Info ( Published February 18. 2021)

There are basically thirty-four characters in Rudge, of whom fifteen could reasonably be viewed as fifty years or older ( based on my definition of an older adult). Dickens frequently refers to them as 'elderly or old', so this is not in dispute, but on occasions, others could also be classified as 'of uncertain age.' Where the character falls within this category, I have explained why their description and/or friendship or familial relationships give the impression of being in their later years. Where the character is based on a natural person, I have checked the historical record of their birth and what age they would have been in 1780 ( the date of the Gordon Riots).

Additionally, to gauge the traits and roles assigned to them and how far Dickens and Victorians generally attributed them to "old age" derives from the intrinsic character portrayed. (1)

With these caveats, let's meet them and what they tell us about Dickens and early Victorian approaches to age and ageing.

Sir John Chester: Often referred to as "old Mr Chester" and clearly 'past the prime of life'. He was loosely based on the 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694-1773) and was obviously dead by the time of the Gordon Riots. The character is Edward Chester's father, and later, becomes Sir John. There is a "deep and bitter animosity" between him and Geoffrey Haredale, "which is aggravated by Chester being a Protestant and Haredale a Roman Catholic "(2). He is described as a "soft-spoken, delicately made, a precise and elegant gentleman, cold, calculating and scheming."(3) In addition ", he wore a riding coat of a somewhat brighter green that might have been expected of a gentleman of his years, with a short black velvet cape, and laced pocket holes and cuff of linen, which was of the finest kind, worked in a rich pattern at wrists and throat, and scrupulously white."(4) Note that his dress was viewed as age-inappropriate.

Chester is a villain, coercively controlling towards his son and manipulative towards Hugh and evicts Edward from the house. Gabriel Varden confronts Sir John with the revelation that "Hugh was his illegitimate son by a gypsy woman who he had abandoned and who had been hanged for petty theft" (5)(6)

Unlike the late Earl of Chesterfield, Dickens's portrayal is not of the aristocracy. Still, as in many of his novels, it is of an unsympathetic older parent who thwarted, denied, and abandoned his son. This abusive parent does not repent - he always remains outwardly unruffled, "the same imperturbable, fascinating gentleman of previous days."(7). Apart from the age-inappropriate quip, does Dickens's evidence of ageism? I think not. Instead, if we use Berman Nelsons's analysis of Voltaire's portrayal of old age, Chester reflects as an old man who had power due to his social standing, relative wealth and egotistically obsessed wanting his son to marry into wealth that would contribute to securing his own lifestyle. (8) One is reminded of Ralf Nickleby, who abandoned his son Smike and came to a sticky end! (9)

Mr Chesters's Chair. Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz). Woodcut, Chapman and Hall (1841)

Death of Sir John. George Cattermole.Woodcut. Chapman & Hall (1841)

Tom Cobb: Although of uncertain age, he is a general Chantler and Post Office keeper in Chigwell, Essex. He is a cronie and sidekick of old John Willetts, Solomon Daisy and Long Phil Parks at the Maypole Inn. It may be a stretch to assume he is fifty-plus, and they were all of the same generation, but the term chronic implies that they were all of a certain age. Regulars at local public houses tend to be. His description doesn't really help us. I simply felt uncomfortable to have discounted him entirely. I am sure Dickensian scholars will put me right!

Ned Dennis: (Tyburn Hangman). Again, it may be a supposition on my part to include him in this listing. My rationale is based on his occupation, being a natural person, and the fact that by the time Dickens was writing, attitudes to public hanging were changing. Above all, the description and imagery given in Rudge are telling. The words and phrases speak for themselves: "A squat, thick set personage, with a low forehead, a course shock of red hair, and eyes so small and near together that his broken nose alone seemed to prevent their meeting and fusing into one of usual size. A dingy handkerchief twisted like a cord about his neck - his dress was of threadbare velveteen - a faded, rusted, whitened black, like ashes of a pipe - in lieu of buckles at his knees, he wore unequal lengths of packed thread" (10)

By the time Dickens wrote Rudge, he was aware of the changing attitudes associated with public executions. The real Edward Dennis (1740-1800) was known to be theatrical and brutal. In 1780, he was not, within our definition, an older adult, and he retired eight years after the Gordon riots and lived until 1800 in reduced financial circumstances. Dickens has his 'Ned Dennis' imprisoned and condemned to death, crying and cowardly until he experiences 'the drop.' Do we feel pity for this thoroughly pathetic character in his last days? Was it Dickens's intention? I think not.

Dennis and Hugh Condemned. (Harry Furness (1910)). Scanned by Philip V. Allingham. (Victorian Webb)

Dennis by Clark, Joseph Clayton (KYD) "Very Good No Bindimh (1920)

Notwithstanding the literary and historical importance of his character and physical attributes, some key terms Dickens uses cannot be ignored if they reflect and generalise 19th-century age and ageing imaging ( 'twisted', 'dingy', 'faded' and 'rusted' ). The illustration above by Furness is clearly an adaption of Phiz's original, "Dennis and Hugh in the Condemned Cell"). Dickens personally selected and agreed to all illustrations in his fiction. The illustration by Furness is reminiscent of Daniel Quilp ( The Old Curiosity Shop), discussed in a previous blog. (11.1) It is also worth reminding ourselves of the meaning of "red hair" during the 19th Century and its inference of antisemitism. (11.2)

Daisy Soloman: Although we are not given his age, there are some indicators from the storyline, relationships, and illustrations, both in the original serialization and subsequently. Soloman is a parish clerk and regular at the Maypole Inn. He tells his cronies, Cobb and Parks, addinfaniteam of the murder of Reuben Rudge and the discovery of his body twenty years previously. He was a direct witness to that discovery. Dickens describes him as having ' little black shiny eyes like beads', and this 'little man wore at the knees of his rusty breeches, a rusty black coat' (12). In narrative terms, it is not of an infirm man, given he, together with Parks and Cobb, 'walks from Chigwell to London to see for themselves what is happening there' (13). The illustration below, however, by Phiz ( and agreed by Dickens) appears to give a different impression.

Soloman enters the Parlour. Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz) .Woodcut. (1840-1)

Sir John Fielding (1721-1780): English Police Magistrate at Bow Street. At the time of the Gordon riots, he was fifty-nine and died in the same year. Brother of the novelist Henry Fielding, commonly called the "Blind Beak." A recognised reformer of the criminal justice system. He championed a better understanding of juvenile offenders, and Dickens would be aware of his attempts to professionalize the role of magistrates and an advocate of understanding the social and economic causes of crime. This resonated with Dickens, who generally regarded the Gordon Riots less as an inter-religious conflict than a statement of social conditions.

Mr Gashford: ( Lord George Gordon's Secretary) At the outset, this character cannot reasonably be within our definition of an older adult. So why include him? I discussed in previous blogs that we need to look at a pattern of portrayals that reflect gerontophobia and/or ageism in his writings. Notwithstanding Dickens's portrayals of children (especially pre-pubescent girls, evidencing ephebophilia) in terms of older adults, the dismal, grotesque, physically disabled, evil, criminal, and exploitative characters are dominant. Dickens throws his net wide, equally capturing these negative characteristics across demographic age groups. Gashford is a case in point.

Hawes comprehensively summarises Gashford's role and description of this 'villainous' character. He was loosely based on Lord George Gordon's biographer, Robert Watson (1746-1838), who claimed to be the Lord's Secretary. This claim is generally disputed. Hawes believes that Dickens would have been very much aware of the Inquest on Watson shortly before he started the serialisation of Rudge and the discovery of Watson's body, which "may have been responsible for Dicken's choice of name for this character ' concluding that the " personality and behaviour" is entirely of Dickens invention. Watson would have been thirty-four at the time of the Gordon riots. An invention that describes Gashford thus: "angularly made, high shouldered, bony, and ungracfull. His dress, imitating his superior, was demure and staid in the extreme; his manner was formal and constrained. This gentleman had an overarching brow, great hands and feet and ears, and a pair of eyes that seemed to have made an unnatural retreat into his head...the man that blows the fire, a servile, false, and trucking knave" (14) The young adult Dickens ( he was aged twenty-five when he started writing Rudge, and at the same time still penning Oliver Twist) showing his narrative brilliance.

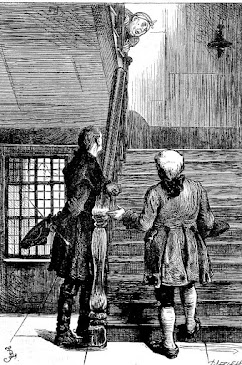

Gashford on the Roof. Hablot Knight Brown (Phiz) Woodcut (1840-1)

Reuben Haredale: Father of Miss Haredale and elder brother of Mr Haredale. "He is not alive, and he is not dead - not dead in the common sort of way..found murdered in his bed chamber, and in his hand was a piece of cord attached to an alarm bell outside the roof."(15) The brutal murder of Reuben, bloody and cruel by the hands of Barnaby's father is probably more critical to the plot than in fact The Gordon Riots. The intra-family dynamics of the Haredales are classic Dickens, which I will refer to later in the series.

Mr Langdale: Here again, Dickens has based his character on a historical figure, Thomas Langdale (1740-90), a well-known distiller and vintner whose premises fell victim to the riots. At the time, he would be aged forty. Dickens, however, refers in his portrayal as a "portly old man, with a very red face, or rather purple... but also a very hearty old fellow and a worthy man" (16). Philip and Gadd's commentary adds that Langdale was a " rubicund, choleric, but a good hearted gentleman" (17). Whatever Dickens had in mind regarding his portrayal, the reference to the description of a forty year old man as "old." is interesting. (18) It goes to the current notion that "age is just a number." Remembering, again, that Dickens was both a novelist and a journalist. This good-hearted character showed anger at the refusal of the Lord Mayor to arrange the transfer of Mr Rudge (senior) and put him in custody, even though he was contained in a coach outside Mansion House.

The illustration by Fred Barnard (1874) below, and the always valuable commentary of the Victorian Webb, shows the cowardly Mayor in his nightshirt refusing the aristocratic Haredale and the middle class Langdale pleading to arrest and put Rudge in prison. It was, says the Victorian Webb, a result of both being Catholics. It reflects Dickens's political satire of public officials who were afraid; in this instance, the mob supported Gordon's call for "No Popery" (19). Political satire should, in the pen of Dickens, its master, always be factored in officialdom as a process and/or of a particular character. It asks if Victorian age stereotypes intersect with how Dickens portrayed his older characters. In this case, being based on a natural person who happened to be forty years old.

Mr Rudge: Steward of Reuben Haredale and father of Barnaby Rudge, who murders his employer for financial gain, in fact, robbery! In addition, he murders Haredale's gardener whilst escaping from the house, who is subsequently believed to be that of Rudge himself. Unsurprisingly, he goes on the run but returns decades later as the Stranger in the bar of the Maypole Inn and is now aged "sixty or thereabouts." Dickens described him as having " hard features..much weather-beaten and worn by time, and the naturally harsh expression was not improved by a dark handkerchief bound tightly around his head. His face scarred and his complexion of a hard hue." (20).

Together with Stagg, he tries to now exploit his wife, whom he had abandoned and later would be imprisoned with her. Mrs Rudge is keen for him to 'repent' but true to form this dastardly character aggressively "in a paroxysm of wrath, and terror, and the fear of death ...rushes into the darkness of his cell...casts himself jangling down upon the stone floor, and smote it with his iron hands" (21) Yet again, Dickens, as he had done with numerous older characters throughout his literature has the older unrepentant ( and even the repentant) facing a justified end, this time by the hangman. A good Victorian riddance!

It could be argued, however, that Rudge's age was irrelevant, given his lifetime of criminality (e.g. Fagin). It again demonstrates Victorian beliefs and approaches to crime and punishment of the criminal classes, which, as Clive Emsley highlights, Dickens himself 'helped shape popular conceptions' (22). Older criminals were considered unreformable, whereas young male adolescents were. Indeed, in Dickens's numerous family sagas, they were, by and large, older adults who were exploited, robbed, abandoned, abused and murdered, whilst the stereotypical girl or woman was seen as a victim or in need of 'psychiatric treatment' and confined in asylums rather than prison. Dickens was a rescuer of females, both in his writings and life. The intersections of gender, sexuality, criminology and ageism come into play throughout the Victorian age. He advocated prisons and transportation ( ended in the mid-1850s). Older male criminals were 'incorrigible' as were some older male parents and guardians within families, but older female characters could be bad, maybe mad, harsh and unfeeling, but seldom criminal.

It could be said that he, in today's terms, 'exploited' - female sex workers whilst also opening Urana Cottage, a refuge for them in 1847. His motivation has been a matter of debate amongst Dickensian scholars. I'll leave it there.

Barnaby and his father. Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz)

WoodcutChapman & Hall 1840-1

However, there is an additional point when we explore the parenting of Barnaby by his father - it was nonexistent. It cast a sinister shadow over him. In several of his characterizations, Dickens demonstrated their ego-centricity, of which Mr Rudge, according to Dr Archana Gautam, was arguably "the most outstanding" (23). Gautam examined several of Dickens's egocentric parents where children "suffer at the hands of their own callous and uncaring, and selfish parents and demanding parents", adding that 'mothers are odd and fathers bad.' Mr Rudge was killed on the very day Barnaby was born, adding that "in the eyes of his murderous father, it is as if the baby son... sprung from his victim's blood." In the many examples of wicked, evil, neglectful, and murderous fathers, there is a dynamic in the Rudge son/father dynamic ( literary and personal) that the parent must suffer and pay for their behaviour (24). Their age is perhaps irrelevant, but it is interesting from a literary gerontological perspective that the debt is paid in full in their later adult years - an untimely but deserved death.

At this juncture, it is worth considering the relationship between Chester and his son Edward, which has been the focus of a study that emphasises Chester's refusal to take parental responsibility, shaping the father and son relationships in Barnaby (25). The representation of father figures towards their children is a common theme Dickens reflected in his early ( and even later) novels. Here, they mirrored Mr Rudge's senor in the characters of Barnaby and Chester with Edward. These older characters do not accept responsibility. Bergh-Seeley talks about "the dark halves in Dickens's writing" (26), which I would suggest reflected the two sides of Dickens himself. Youth and its Portrayal v's that of Old Age

Revisiting Gabriel Varden and introducing his Mrs Martha Varden as "of uncertain temper."

Gabriel Varden with Miggs and his wife Martha